In this essay, I critically comment on the Buddhist ‘five skandhas’ doctrine. This doctrine is attributed to the Buddha himself and considered as a core belief of Buddhism[1]. However, in my humble opinion, in view of its evident intellectual limitations, this doctrine should not be given such elevated status. Buddhism and its founder have much more intelligent ideas to offer the world. That being the case, the present critique of the five skandhas doctrine should not be taken as a general critique of Buddhism or its founder.

Although often listed in the literature, the five skandhas are rarely clearly defined and expounded on. The Sanskrit word skandha (Pali: khanda) means ‘aggregate’ – and apparently refers to a building-block, of the mind or perhaps of the world. In Sanskrit, the five skandhas listed are: rupa, vedana, samjna, samskara, vijnana (in Pali: rupa, vedana, sanna, sankhara, vinnana). In the dozens of English texts that I have read over the years, I have seen these terms translated in various ways, and with rare exceptions barely explained. It is not made clear whether these terms are essentially phenomenological, psychological, metaphysical, ontological or epistemological. When interpretations are proposed, they differ considerably from one text to another. Nevertheless, this being an important doctrine in Buddhism, it is worth analyzing and evaluating.

1. My Own Phenomenological Reading

Before studying the normative interpretations of these terms, permit me to present my own initial interpretations, even while admitting that they are largely inaccurate historically. That way, the reader will know where I am coming from, and will be better able to follow my thinking. When I first came across the five skandhas in Buddhist books, I took them to constitute a sort of phenomenology, i.e. a list of the different categories of being or appearance, one that suggests an ontological and epistemological theory insofar as the list distinguishes and interrelates the categories in certain ways. Consider the following reading:

- Rupa, usually translated as ‘form’, could be taken to refer to the apparently external and material world, which contains the phenomena of all shapes and sizes in motion that we seem to witness through our senses, the senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch. This field of experience is quantitatively overwhelming, and takes up most of our existence, but is of course not the whole story, not the whole of our world.

- Vedana, usually translated as ‘sensation or feeling’, could be taken to refer more specifically to the phenomena we experience as within our personal body. In a sense, these are part of the external and material world, since our body is apparently part of it; but in another sense, they are closer to home (i.e. more internal) and less material (i.e. containing some phenomena notably different from those we experience further afield). In this context, our touch sensations of bodies beyond our own body are feelings, as are all the myriad physical sensations we experience within our bodies, such as sexual feelings (desire, satisfaction), digestive feelings (hunger, thirst, satiety, stomach aches, sensations when urinating or defecating, etc.), and feelings in other internal organs (headaches, heart beats, heartburn, muscular cramps, nerve pains, etc.). Here would also be included emotional reactions experienced within the body, such as love (a flutter or warmth in the heart region), fear (a flutter or warmth in the stomach region), etc. In short, all the pleasures and pains we may be subject to within our bodies, whether they stem from physical or mental causes. Also to be included under this heading would be our sensations of volition (acts of will), i.e. the sense we have that we move our body parts around and our whole body through space; and therefore also our sensations of velleity (pre-volitions, attitudes, intentions). Note however that, while volitions and intentions may have phenomenal aspects, they are largely non-phenomenal; i.e. they are intuited rather than perceived.

- Samskara, usually translated as ‘mental formations’, and sometimes as ‘impulses to volition’, could be taken to refer to the inner phenomena we experience through our faculties of memory and imagination (the latter being voluntary or involuntary manipulation of memory items to produce somewhat new images, sounds, etc.). This includes the images of visualizations, the sounds of verbal thoughts, dreams (during sleep) and hallucinations (the latter being stronger projections, apparently into the space where matter resides, of imaginations). These phenomena resemble those experienced as external and material, in that they also have shape, color, sound, etc., and yet are experienced as substantially different, of a different ‘stuff’, so much so that we give them a different name (they are characterized as mental, as opposed to material), even if we do regard the mental phenomena, or phantasms, as derivatives of the material ones (through memory of experiences). Such mental phenomena obviously can and do condition (variously incite or otherwise affect) subsequent more overt actions.

- Samjna, usually translated as ‘perception’, but often as ‘apperception’, ‘conception’ or ‘cognition’, could be taken to refer to our various objects of cognition, i.e. whatever we intuit (non-phenomenal concretes), whatever we perceive apparently through the physical senses or mentally through memory and imagination (phenomenal concretes), and all the abstractions and theories (based on the preceding items) that we construct through conceptual insight and reasoning (including negation, similarity, dissimilarity, etc.). Thus, samjna would include our non-phenomenal impressions (apperceptions), our phenomenal experiences (perceptions), and the concepts and thoughts (conceptions) emerging from the preceding through which we get, not merely to experience things, but also to order and interrelate them, and thus to understand them (or be confused by them) to various degrees. Thus, note well, samjna focuses on objects in the context of their being cognized, i.e. as contents of cognition (and not as objects apart from cognition).

- Vijnana, usually translated as ‘consciousness’, could be taken to refer to the fact of cognition, the cognizing, as against its object (content), and its subject (the self apparently doing the cognizing). Consciousness has to be listed separately because it is substantially different from any of the other categories in our enumeration. Note well that, to assure a complete enumeration, this term in my view would have to include both the relation of cognition and the apparent self or soul which is related by it to the object. This refers to the self which we all routinely intuit – even though Buddhists deny the latter’s reality and consider it as illusory. This understanding is not entirely foreign to Buddhist practice, which tends to use the terms ‘consciousness’ and ‘mind’ in an ambiguous manner that sometimes really (though typically without frankly admitting it) intends the self (i.e. the one who is conscious)[2]. Moreover, it should be stressed that the self not only cognizes, but also wills and values – i.e. that volition and valuation are among its powers as well as cognition, and that these three faculties are interdependent and do not exist without each other.

That is to say in our present perspective: while rupa refers to external and material objects, vedana to more specifically bodily objects, and samskara to mental objects, and while samjna identifies these same categories of objects as contents of cognitive acts, vijnana refers to the implied knowing (and willing and valuing) acts and to the spiritual entities (ourselves) apparently engaged in them. From this we see that the various phenomenological categories here enumerated overlap somewhat: rupa includes at least part of vedana, samskara is a side-effect of rupa and vedana, samjna includes the preceding experiences and adds their more complex conceptual and rational products, while vijnana focuses on the subject and the relationship of consciousness (and volition and valuation) between it and these various concrete and abstract objects.[3]

The above phenomenological account is merely, to repeat, my personal projection: it is the way I have in the past tended to interpret the five skandhas doctrine in view of the terminology used for it in English. This is the way I, given my own philosophical background, would build a theory of knowledge and being if I was forced to use these five given terms, even while aware that such theory contains some non-orthodox perspectives.

2. A More Orthodox Psychological Reading

However, Buddhists and other commentators present these terms in a rather different light. I will use as my springboard an interesting account I have seen on this topic by Caroline Brazier in Buddhist Psychology. Let us first look at this psychological approach, which I think is close to the original intent of the five skandhas doctrine, given that Buddhism is concerned with ‘enlightening and liberating’ people rather than with merely informing them to satisfy their curiosity. She writes:

“The skandhas are the stages in a process whereby the self-prison is created and maintained. At each stage, perception is infiltrated by personal agendas that create distortion. Delusion predominates…. Each of us continually seeks affirmation that we are that person who we have assumed ourselves to be. Situations that disturb this process are avoided or reinterpreted, and the self appears to become more substantial” (pp. 92-93).

Her exposition of the stages is as follows (summarily put, paraphrasing her). The first stage is rupa, which is finding indications of self in everything we come in contact with; i.e. grasping onto all sorts of things because they reinforce our belief in having a self, and indeed one with a specific identity we are attached to. Next in the process comes vedana, which refers to our immediate value-judgments in relation to things that we come across (people, events, whatever); we may find them attractive, repulsive or confusing – but in any case, we have a visceral reaction to them that affects our subsequent responses to them. Thirdly comes samjna, which consists in spinning further fantasies and thoughts around the things we have already encountered and initially reacted to; due to this, we are unconsciously carried off into certain habitual behavior-patterns. Samskara refers to these action and thought responses which we have, through repetitive past choices, conditioned ourselves into doing almost automatically. Finally comes vijnana, which refers more broadly to the mentality (perspectives and policies) we adopt to ensure our self is well-endowed and protected in all circumstances.

These five stages constitute a vicious circle, in that the later stages affect and reinforce the earlier ones. They ensure that we enter and remain stuck in the cycle of birth, suffering and death. The important thing to note is that the purpose of this psychological description is to make us aware of the ways we ordinarily operate, so that we may over time learn to control and change those ways, and become enlightened and liberated. As Brazier puts it: “Buddhism is not a matter of just going with the flow. It is about changing course” (p. 95). In this approach, the skandhas doctrine is a practical rather than theoretical one. It is a ‘skillful means’, rather than an academic exposition. It is concerned with the ways we commonly form and maintain of our ‘self’.

Needless to say, this looks like a very penetrating and valuable teaching[4]. The question for us to ask at this point, however, is whether it is entirely correct. That is to say, assuming the above sketch is an accurate rendition of the Buddhist theory of human psychology, is this the way we ordinary (unenlightened, unliberated) human beings actually function? Brazier, being a committed Buddhist, takes this for granted rather uncritically. I would answer that though this theory seems partially correct, it is certainly not fully so. What we have here, at first sight, is a portrait of someone who is (very roughly put): very narrow-minded (rupa), instinctive (vedana), irrational (samjna), habitual (samskara), and selfish (vijnana). This may fully describe some people, and it may partly describe all of us, but it is certainly not a complete picture of the ordinary human psyche.

What is manifestly missing in this portrait are the higher faculties of human beings – their intelligence, their reason and their freewill. It could be argued that these higher faculties are present in the background, in the implication that people can (and occasionally do) become aware of their said lowly psychological behavior and make an effort to overcome it. But if so, this should be explicitly included in the description. That is to say, intelligence, reason and freewill should be presented as additional skandhas. But they are not so presented – it is not made clear that humans can function more wisely, and look at the facts of a situation objectively and intelligently, and decide through conscious reasoning how to best respond, and proceed with conscious volition to do so. In any case, these higher faculties are routinely used by most people, and not just used for the purpose of attaining enlightenment and liberation.

Why are these higher faculties, which are common enough, even if to varying degrees, not mentioned in the Buddhist account as integral factors of the human psyche? I would suggest that the main reason is that the self (or soul) has to be dogmatically kept out of it[5]. The central pillar of the Buddhist theory of enlightenment and liberation is that our belief that we have a self is the deep cause of all our suffering, because a self is necessarily attached to its own existence, and the way out of this suffering is to realize that we do not really have a self and so do not need to attach to anything. In such a context, the human psyche must necessarily be described as essentially reactive and stupid, like a ship without a helmsman, at the mercy of every wind and current. Buddhism does regard humans as able to transcend these limitations, by following the ways and means taught by the Buddha in the Dharma; but it does not (in my opinion) fully clarify the psychological processes involved in self-improvement, no doubt due to the impossibility of verbally describing them with precision and generality.

Brazier does go on to describe how Buddhist psychology conceives transcending of the skandhas. She does so in terms of the ‘five omnipresent factors’ being transformed into ‘five rare factors’ “through spiritual practice.” But of course, that account does not clearly say who is doing the spiritual practice, and what faculties are involved. It does not acknowledge that the individual person involved (the self) has to realize (through intelligence and reason) the need for and way to such transformation, and then proceed to bring it about (through complex volitional thoughts and actions). The self and its higher faculties are not given due recognition (because, as already explained, such recognition would go against the Buddhist dogma of no-self). This is not a fault found only in Brazier’s account, but in all orthodox Buddhist accounts.

Understandably, Buddhism, particularly its Zen branch, rejects excessive intellectualism. Admittedly, intelligence, reason and freewill are all very well in principle, as tools for human betterment; but used in excess – or simply misused or abused – they can also and often do exacerbate human delusion and suffering. The intellect can be compulsively used to weave complex webs that distance its victim from reality rather than bring him or her closer to it. We can by such excess become more and more artificial and divorced from our true nature. Of that danger there is no doubt; it is observable. But intellectualism is surely not the whole story concerning our said higher faculties. Surely, they play a big role in improving our understanding and behavior, both in everyday life and in longer-term more intentionally spiritual pursuits.

Moreover, we have to ask whether the five skandhas doctrine, even taken at face value, is truly consistent. We are told that rupa consists in viewing things in relation to self rather than objectively, that vedana consists in immediate likes or dislikes, that samjna consists in making up associations, that samskara consists in conditioning, and that vijnana consists in selfish mentality – and it is all made to seem simple and mechanical. But is it? The Buddhist account itself tells us that these events are interrelated, i.e. stages in a process. Therefore, beneath each of them there must be complex mechanisms at play. Rupa must involve a certain sense of self and of its identity, to be able to select information of interest. Vedana, however instantaneous it may seem, cannot be immediate since it must be filtered through the subconscious scale of values of the person concerned. Samjna presupposes that there are older mental contents to which it associates new mental contents. Samskara refers to habits, which imply programming by repetition. And vijnana in turn implies storage of information and of valuations.

Furthermore, even if we grant that the five skandhas reflect common tendencies within the human psyche, it is introspectively evident that normally the self can in fact, at every one of these stages, intervene through free will based on rational considerations and conscious valuations. That is to say, faced with the ego-centricity of rupa, we can still choose to view things more objectively; faced with thoughtless valuations of vedana, we can still choose to evaluate things in a more balanced manner; faced with wild associations of samjna, we can still choose to put things in context more accurately; faced with our bad samskara habits, we can still choose to resist temptations or overpower resistances; faced with native vijnana selfishness, we can still choose to act with larger perspectives in mind. The human psyche is not a mechanical doll, driven by forces beyond control – there is a responsible soul at its center, able (whether immediately or gradually) to impose its will on the rest of the psyche. Buddhists cannot consistently deny all this, since they do believe in and advocate self-improvement, as the Noble Eightfold Path makes clear.

This brings us to the crux of the matter, the determinism tacitly involved in the five skandhas doctrine. The skandhas are imagined by Buddhists as dharmas, i.e. as “a series of consecutive impersonal momentary events,” as Vasubandhu put it[6]. No one is making them happen, they just happen each one caused by the ones preceding it and causing the ones succeeding it. They do not happen to someone, either, even if they seem to. They are “linked to suffering,” but no one suffers them. Clearly, there is logically no room, in this conception of psychological processes, for a person actually cognizing, understanding, evaluating, reasoning, deciding, choosing and engaging in action. Not only is the person removed, but the acts of cognition, valuation and volition are also removed. They are reduced to mere momentary electrical disturbances in the mental cloud[7], as it were. They are no longer special relations between a subject or author and other things in the mind or body. This doctrine is, really, crass reification of things that are definitely not entities.

The five skandhas is clearly a mechanistic thesis, even if it is mitigated in a subterranean manner by the Buddhist faith in the possibility of enlightenment and liberation. In this view, logically, such spiritual attainment is itself merely the product of a chain of impersonal mental events, with no one initiating them and no one profiting from them[8]. This state of affairs is claimed to be known by means ‘deep meditation’, although it is not made clear who is doing the meditating, nor by means of what faculties or for what useful purpose. Clearly, objectively, however deep such meditation it could not possibly guarantee the verity of the alleged insights, but must needs submit them to logical evaluation in accord with the laws of thought. Scientific thought cannot accept any deep insights, or any revelations based on them, at face value; it demands rational assessment of all claims.

In truth, granting that there is some truth to the psychological processes described by the skandhas doctrine, they must be viewed more restrictively as processes of ego-building, rather than so radically as processes of self-invention. They refer, not to ways that ‘we’ (a never explained yet still repeatedly used grammatical subject) imagine the self or soul to exist, but to ways that we (the truly existing soul, our real self) construct and maintain a particular self-image that we think flattering or securing. What is evident in honest, non-dogmatic meditation is that, while such processes can surely influence our mental and physical behavior, i.e. make things easier or more difficult for us, they do not normally determine it. An influence, however strong, can always (with the appropriate attitude and effort) be overcome. At almost every moment of our existence, we remain free to choose to resist these mental forces or to give in to them. If we but make the effort to be aware, to judge and to intervene as well as we can, we remain or become effective masters of our fate.

It is only because we indeed exist as individuals, and have these powers of cognition, valuation and volition, that we can observe, identify, understand and overcome the impersonal forces described by the five skandhas doctrine. Therefore, in fact, the said doctrine, far from constituting an exhaustive listing of the basic building blocks of the human psyche, at best depicts just some surface aspects of much more complicated events and structures. Not only is the list incomplete in that it lacks overt reference to the human self and its higher faculties, but additionally its presentation of the five lower faculties (even assuming that these five faculties indeed exist) is rather superficial. For all the above reasons, and yet others, I view the five skandhas account of human psychology as deficient.

As regards enlightenment, liberation and wisdom, these are impossible without a soul and its faculties of cognition, volition and valuation. Enlightenment means perfect cognition by the soul, i.e. a consciousness as high, wide and deep and accurate as can be for the person concerned. Liberation means perfect volition by the soul, i.e. a will as free of obstructions and as powerful as can be for the person concerned. Wisdom means perfect valuation by the soul, meaning full understanding of good and bad coupled with behavior that is accordingly fully virtuous and non-vicious. Enlightenment, liberation and wisdom are concepts only applicable to sentient beings (notably to humans and other animals, and perhaps in some sense to plants); they are irrelevant to non-spiritual entities (i.e. material and/or mental entities devoid of soul, such as skandhas, computers or fantasy creatures).

3. The Metaphysical Aspects

The Encyclopaedia Britannica (EB) defines the skandhas as “the five elements that sum up the whole of an individual’s mental and physical existence.” It lists them as “(1) matter, or body, the manifest form of the four elements—earth, air, fire, and water; (2) sensations, or feelings; (3) perceptions of sense objects; (4) mental formations; and (5) awareness, or consciousness, of the other three mental aggregates [i.e. items 2-4].”

In most accounts I have seen, this theory is presented as descriptive of what constitutes a person. Some accounts I have seen, however, apply it more broadly, viewing the five skandhas as the constituents of the phenomenal world. In any case, this theory clearly contains an ontological thesis, insofar as it acknowledges two kinds of phenomena, the material (the first skandha) and the mental (the other four skandhas)[9]. Moreover, note in passing, since the above definition mentions the ‘four elements’, it includes a physical theory, one admittedly very vague and by today’s standards rather useless[10]. Secondly, the skandhas doctrine has some epistemological implications, in that it identifies sensations or feelings, perception of sense objects, and so on – implying our ability to know of such things, presumably by introspection.

Furthermore, the said source (EB) explains that “The self (or soul) cannot be identified with any one of the parts, nor is it the total of the parts. All individuals are subject to constant change, as the elements of consciousness are never the same, and man may be compared to a river, which retains an identity, though the drops of water that make it up are different from one moment to the next.” This statement is the metaphysical element in the skandhas doctrine, since it involves important claims regarding the ultimate nature of individuals (i.e. persons, people).

This explanation reminds us that the philosophical motive of the skandhas doctrine is to buttress the Buddhist claim that we have no self or soul (anatta). According to this doctrine, we are only clusters of the listed five material and mental phenomena, which are in constant flux, unfolding as a succession of events, each new event being caused by those before it and causing those after it. It is stressed that none of the skandhas is the self, and neither is their sum the self. The self is not something apart from them, either. What we call the self is a mere illusion, due to our conflating these ongoing, causally-linked events and giving them a name.

The no-self idea is usually expressed by saying that the human being is ‘empty of self’. This is presented as one aspect of a wider metaphysical doctrine of ultimate ‘emptiness’ (shunyata), applicable to all things in the phenomenal world. Initially, I suggest, Buddhist thought sought to replace the self we all naturally assume we have with the five skandhas. Since the doctrine of ultimate emptiness needed to be applied to the apparent self, an explanation of apparent selfhood was provided through the doctrine of the five skandhas. The self does not really exist; it is only made to appear to exist due to the play and interplay of the five skandhas. However, consistency required that the five skandhas be empty too. This was later acknowledged, for instance, in The Heart of the Prajnaparamita Sutra, which stated:

“Form is emptiness, emptiness is form… The same is true with feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness.”[11]

Here, the five skandhas, thanks to which the self seems to us to exist even though it is in fact empty, are affirmed to be empty too, note well. All phenomenal existents are empty, and this includes the skandhas too. The question might then well be asked (by me, at least): if the skandhas are equally empty, what ideological need have we of them? Why can we not just as well admit the existence of the self or soul, and call it ‘empty’ too, directly? This is of course a significant flaw in the doctrine of the skandhas – it shows the idea of them to be logically redundant. If the motive behind it was to explain the emptiness of self, it was not only unnecessary but useless, since the emptiness of skandhas also had to be admitted! Logically, far from simplifying things, the skandhas hypothesis complicated them.

In other words, the Heart Sutra could equally well have stated: “self is emptiness, and emptiness is self;” or even: “soul is emptiness, and emptiness is soul.” And indeed, it could be argued that soul, being more insubstantial (less phenomenal) than the skandhas, is closer to emptiness than the skandhas are. There are obviously two concepts here to clarify – (a) soul and (b) emptiness. Additionally, we must (c) examine their interrelation.

(a) The term soul refers to an entity of spiritual substance, i.e. of a substance other than the substances that material or mental things seem to have. Soul has no phenomenal characteristics – no shape or color, no sound, no flavor, no odor, no hardness or softness, no heat or cold, etc. That is to say, it cannot be cognized by external perception (using the five sense organs) or by internal perception (using the proverbial mind’s eye, and its analogues, the mind’s ear, etc.). This does not mean it cannot be cognized by some other, appropriate means – which we can refer to as apperception or intuition.

Just because the soul is not phenomenal, it does not follow that it does not exist. Buddhists apparently cannot understand this line of reasoning. In the West, David Hume (Scotland, 1711-76) evidently had the same problem. Looking into himself, he could only perceive images and thoughts, but no soul. Obviously, if you look for something in the wrong place or in the wrong way, you won’t find it. If you look for something non-phenomenal in a field of phenomena, you won’t find it. If you look for color with your ears or for sound with your nose, you won’t find them. To look for the soul, you just need to be intuitively aware. All of us are constantly self-aware, even though we cannot precisely pinpoint where that self is. There is no need for advanced meditation methods to be aware of one’s soul – it is a common, routine occurrence.

Note well that I am not affirming like René Descartes (France, 1596-1650) that soul is known through some sort of inference, namely the famous cogito ergo sum, i.e. “I think therefore I am.” We obviously can and do know about the soul through such rational means, i.e. through abstract theorizing – but our primary and main source of knowledge of the soul is through direct personal experience, which may be referred to as apperception or intuition. So, my approach is not exclusively rationalist, but largely empiricist. In this, note well, my doctrine of the soul differs radically from the Cartesian – as well as from the Buddhist.

According to Buddhist dogma, one cannot perceive the soul in meditation; if one observes attentively one only finds various mental phenomena (the five skandhas, to be exact). But I reply that the soul is manifestly a non-phenomenal object and should not be conflated with such overt phenomena. We all have a more or less distinct ‘sense of self’ most if not all of the time, without need of meditation.

This is obvious from the very fact that everyone understands the word ‘self’. Buddhism admits this sense of self, but absurdly – quite dogmatically – takes it to be ‘illusory’. Having at the outset dismissed this significant ‘sense’ (intuition) as irrelevant, it is not surprising that it cannot find the soul (i.e. the human self) in the midst of the phenomena of mind (the five skandhas)! Note this well – Buddhism has no credible argument to back its no-soul thesis. It begs the question, calling the sense of self illusory because it believes there is no self, and claiming that it knows by introspection that there is no self while rejecting offhand the ordinary experience of self we all have. As a result of this manifest error of reasoning, if not outright doctrinaire dishonesty, Buddhism becomes embroiled in many logical absurdities.

Just as one would not look for visual phenomena with one’s hearing faculty or for auditory phenomena with one’s visual faculty, so it is absurd to look for spiritual things (the soul, and its many acts of consciousness, will and valuation) with one’s senses or by observing mental phenomena. Each kind of appearance has its appropriate organ(s) of knowledge. For spiritual things, only intuition (or apperception) is appropriate.

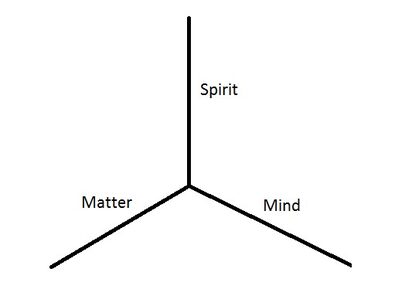

To understand how the soul can exist apparently in midst of the body and mind (i.e. of bodily and mental phenomena) and yet be invisible, inaudible, etc. (i.e. non-phenomenal), just imagine a three-dimensional space (see illustration below). Say that two dimensions represent matter and mind and the third applies to spirit. Obviously, the phenomena of mind will not be found in the matter dimension, or vice versa. Similarly, the soul cannot be found in the dimensions of matter and/or mind, irrespective of how much you look for it there. Why? Simply because its place is elsewhere – in the spiritual dimension, which is perpendicular to the other two. Thus, it is quite legitimate to claim awareness of the soul even while admitting that it has no phenomenal (matter-mind) characteristics.

Figure 5. Matter, mind and spirit presented as three dimensions of existence.

Note well that the above illustration of the spiritual as located in another dimension is intended as merely figurative, and not to be taken literally, because the concept of dimensions is itself a material-mental concept based on the perception and projection of space. Even the idea of time as a fourth dimension relative to the three dimensions of space is mere analogy; all the more so, the idea of spirit as a further dimension (or maybe a set of dimensions) is somewhat artificial. The simple truth is that spirit cannot really or fully be expressed in material or mental terms, being so very different, truly sui generis. We might likewise object to the image of mind as a distinct dimension (or set of them) in comparison to matter, but mind does have some phenomenal characteristics in common with matter whereas spirit cannot be said to be at all phenomenal. So, to repeat, the above analysis of these three domains with reference to dimensions is merely a convenient metaphor.

Furthermore, it would be epistemologically quite legitimate to claim the existence of soul on purely abstract, conceptual grounds. This is justifiable with reference to the principles of adduction. One can hypothesize an entity, if such assumption serves to explain various observable concrete phenomena. In the case of soul, the ‘phenomena’ involved are our commonplace experiences of cognition, volition and valuation. These experiences are largely intuitive too, but they make their manifest mark in the fields of mind and body. We experience cognition whenever we perceive or conceive anything. We experience volition whenever we think or do anything. We experience valuation whenever we like or dislike anything. Soul explains all these experiences by means of a central entity. This is akin to, say, in astronomy, discovering a planet invisible to our telescopes by observing the displacement of other celestial bodies around it. This is inductive logic.

But in truth, soul is not a mere abstraction; it is a concrete (though spiritual) thing that can be cognized directly using our inner faculty of intuition, to repeat. One error Buddhists make is to confuse entity and essence. The claim of a soul is not a claim of essence, but of entity. The soul is not the essence of the body, or even of the body-mind complex – it is a distinct entity that resides, somehow, in the midst of these phenomena, and affects them and is influenced (and perhaps also affected) by them, but does not have the same nature as them. It is a substance, but a very different and insubstantial substance, as already pointed out. Indeed, to call soul an entity or substance is really just metaphor – analogical thinking. In truth, soul is so different from the other constituents of the world that it can only be described by means of analogy – it cannot really be reduced to anything else we know of.

We can see the said philosophical error made, for instance, in the Milinda-panha, a non-canonical but orthodox Theravada (Pali) text[12]. Here, Milinda questions Nagasena, after the latter claims not to really exist. He asks him very pertinent questions such as who, then, is it that eats, engages in spiritual practices, keeps morality, gains merit, etc. The latter replies by giving the example of a chariot, pointing out that no part of the chariot can be considered as the chariot, nor even the combination of all the parts. Milinda, whose questions were excellent, is very easily taken in by Nagasena’s answers. But (to my mind) we need not be.

For a start, a chariot cannot be considered as analogous to a person. We do not look upon a chariot as like a person, for the simple reason that it does not have capacities of cognition, volition and valuation. To look for the analogue of a soul in a chariot is to commit the red herring fallacy. Moreover, while it is true that a chariot contains no ‘core entity’ which can be so called, and it is true that no one part or combination of its parts can be used to define it, it still has an ‘essence’. A chariot, as a man-made object, is defined by means of its purpose or utility – as a horse-drawn carriage, used for transport and travel, especially in war or hunting or racing. Its essence is an abstraction, not a concrete entity. Certainly, all the required parts must be there to form a functioning chariot, but these parts can be changed at will for other parts like them (though not for other parts unlike them: e.g. one cannot replace a wheel with a shoe). The one constant in it is the said abstract purpose or utility.[13]

The same reasoning does not apply to persons, obviously. So, Nagasena’s argument was in fact beside the point. As already mentioned, a soul is not an essence, but a core (spiritual) entity. It therefore cannot be viewed as one of the five skandhas, nor as the sum of those skandhas, as the Buddhists rightly insist. It can, however, contrary to Buddhist dogma, be viewed as one of the parts of the complete person, namely the spiritual part; but more precisely, it should be viewed as the core entity, i.e. as the specific part that exclusively gives the whole a personality, or selfhood. This is especially true if we start wondering where our soul came from when we were born, whether it continues to exist after we die, where it goes if it does endure, whether it is perishable, and so forth.

This brings us to the question as to whether the soul is eternal or temporary, or (in more Western terminology) whether the soul is immortal or mortal. Eternal would mean that it has existed since the beginning of time and will exist till the end of time. Temporary would mean any shorter period of time, though it may be very long indeed. Temporary could mean as long as the current body lives, or it could mean for many lifetimes – and that with or without physical bodies.

It seems that Indian philosophy had no place for temporary souls, only eternal souls or no-souls – with regard to soul, it was all or nothing[14]. However, this disjunction is philosophically untenable. It is conceivable that the soul is an epiphenomenon of the living human (and more broadly animal, or at least higher animal) body, which comes into existence with it and ceases to exist when it does. Or it may be that this temporary soul lasts longer, transmigrating from body to body or maybe existing without a body. We do not know (at least, I don’t); but what is sure is that these are conceptual possibilities that cannot be ignored. Certainly, non-Buddhist humanity has found them conceivable, since many religions are based on such alternative beliefs.

As regards the eternal soul, the question is whether such a soul can or cannot be liberated from the (alleged) cycle of birth and death. Does eternity of the soul logically imply its eternal imprisonment in suffering? I do not see why. It is conceivable that the eternal soul was once happy, then somehow fell into suffering, but can still pull itself out of its predicament through spiritual practices. It may well be, even, that its liberation depends on a spiritual program like the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism; i.e. on realizing that it is in a vicious circle of suffering, that this suffering is caused by attachment and can be cured by non-attachment, and that such non-attachment can be cultivated through the Noble Eightfold Path. So, there is nothing inherently contradictory to Buddhism in the assertion of an eternal soul. I am not advocating this, only pointing out that it can consistently be advocated contrary to established dogma.

What is sure, in any case, is that the no-soul idea is logically untenable. Buddhists have never squarely faced the logical problems it raises and honestly tried to solve them. They are always inhibited by the fear of being regarded by their peers as heretical holders of ‘false views’; so, they keep repeating the no-soul catechism and keep trying to justify it (using absurd means such as the tetralemma, which puts forward the nutty idea that something can both be and not-be, or that something can both not-be and not-not-be). The use of the five skandhas doctrine as an explanation of the (alleged) illusion of selfhood simply does not convince any honest observer, as above shown. Buddhist preachers say that individuals should not take Buddhism on faith, but try and think the issues through for themselves, and they will see the logic of it. But when someone does so, and comes to a different conclusion and rejects one of their clichés, they are nonplussed if not hostile.

The truth is that it is impossible to formulate a credible theory of the human psyche without admitting the existence of a soul at its center. Someone has to be suffering and wanting to escape from suffering. A machine-like entity cannot suffer and cannot engage in spiritual practices to overcome suffering. Spiritual practice means, and can only mean, practice by a spiritual entity, i.e. a soul with powers of cognition, volition and valuation. These powers cannot be equated electrical signals in the brain, or to events in the skandhas. They are sui generis, very miraculous and mysterious things, not reducible to mechanical processes. Cognition without consciousness by a subject (a cognizing entity) is a contradiction in terms; volition without a freely willing agent (an actor or doer) is a contradiction in terms; valuation without someone at risk (who stands to gain or lose something) is a contradiction in terms. This is not mere grammar; it is logic.

An important question as regards the soul is whether it is the same throughout its existence, or alternatively it spiritually changes (for better or worse) over time. This issue is important as it could affect responsibility, and reward or punishment (karma, in Buddhism). Granting that the soul is responsible for its acts of will at the time of such actions, is it just for the soul to receive the consequences of such actions at a later time? Should I pay in my old age for the vices of my youth that I no longer indulge in, or get the belated rewards for my youthful virtues even if I no longer have them? If the soul is unchanging through time, the answer would obviously be yes. But if the soul does evolve or devolve over time, the answer might at first sight seem negative. Can it still be said that the same person involved in such case?

Different solutions to this problem might be proposed. First, we should emphasize that much of the karmic load (for good or bad) of our lives is placed in our mental and bodily dimensions, our mind and body. The question here posed is whether some of the karmic load is placed in our spiritual dimension, our soul. If we say that the soul is constant, we must place all apparent spiritual changes related to it in its mental and physical environment. Thus, the same soul as a baby has more limited powers of walking, talking, etc.; as an adult, his intellectual and bodily powers reach their peak; in old age, they gradually deteriorate.

Moreover, if one thinks and acts in a saintly manner, one is likely to have a pleasant inner life and probably outer life too; whereas, if one thinks and acts in a depraved manner, one is likely to have an unpleasant inner life and probably outer life too. But what of in some supposed afterlife, when the soul is without body or mind? The choices a person makes at any given time reflect its total circumstances at that time. If I am the same across time, then in principle if I were put back in the same circumstances I would react the same way to them. This would seem contrary to the principle of free will, which is that whatever the surrounding influences the soul remains free to choose – and is therefore ultimately unpredictable.

A better position to adopt may be that proposed by Buddhism in the context of the five skandhas doctrine. I am referring to ‘the Burden Sutra’ expounded by Vasubandhu[15]:

“The processes which have taken place in the past cause suffering in those which succeed them. The preceding Skandhas are therefore called the ‘burden’, the subsequent ones its ‘bearer’ [of the burden].”

We could adapt the same idea to the soul (instead of the skandhas), and say that since its present existence is caused by its past existence, it is in a real sense at all times a continuation of its past, carrying on not only its existence but also its good and bad karma. In this way, even if the soul (the ‘bearer’) has undergone inner changes, it remains responsible for its past deeds (the ‘burden’). The past becomes cumulatively imbedded in the present and future. In that case, we must ask the question: what changes are possible within a soul? Is it not a unitary thing? Can it conceivably have parts? This would seem to take us back full circle to a psychological description, such as the one proposed in the five skandhas theory!

However, I would suggest that such questions are not appropriate in the spiritual realm, which is not quite comparable to the material and mental realms. The soul, being non-phenomenal, cannot be thought of as having size or shape or even exact location, or as increasing or decreasing in content – these concepts and others like them being drawn from the phenomenal realms. We should rather accept that we cannot describe the soul, any more than we can truly fathom its ultimate workings. Just as cognition, volition and valuation are sui generis world-events, so is the soul too special to fit into any simplistic analogies.

It should be added that the view of the soul here proposed is not very far, in many respects, from the Buddhist notion of Buddha-nature. Consider the following brilliant statements by Son Master Chinul[16]:

“The material body is temporal, having birth and death. The real mind is like space, unending and unchanging….

The material body is a compound of four elements, earth water, fire, and air. Their substance is insentient; how can they perceive or cognize? That which can perceive and cognize has to be your Buddha-nature….

In the eyes, it is called seeing. In the ears, it is called hearing…. In the hands, it grabs and holds. In the feet, it walks and runs…. Perceptives [sic] know this is the Buddha-nature, the essence of enlightenment. Those who do not know call it the soul….

Since it has no form, could it have size? Since it has no size, could it have bounds? Because it has no bounds, it has no inside or outside. Having no inside or outside, it has no far or near. With no far or near, there is no there or here. Since there is no there or here, there is no going or coming. Because there is no going or coming, there is no birth or death. Having no birth or death, it has no past or present….”[17]

Clearly, the “real mind” which is “like space,” the “Buddha-nature” which alone can “perceive and cognize,” that which sees and hears and grabs and walks, i.e. that which is the Subject of acts of consciousness and the Author of volitional acts, corresponds to what we commonly call the soul, even if the said writer refuses to “call it the soul.” It is noteworthy that, despite the Buddhist dogma that cognitive and volitional acts do not imply a self, this writer seems to advocate that they do (even while virtuously denying selfhood). Is then the difference between these concepts merely verbal? I would say not. The idea of the soul suggests individuation (in some realistic sense), whereas that of Buddha-nature has a more universal connotation (with apparent individuality regarded as wholly illusory).

(b) Let us now examine the Buddhist concept of Emptiness. Note at the outset that I make no claim to higher consciousness, and have no interest in engaging in fanciful metaphysical speculations using big words. I write as a logical philosopher, an honest ordinary man intent on finding the truth without frills. By ‘emptiness’, most Buddhists do not mean literal vacuity, or a void (non-existence). It may be that some Hinayana thinkers understood the term that way, but I gather Mahayana thinkers viewed it more positively (or ambiguously) as referring to ‘neither existence nor non-existence’. The latter expression is meant to reject both excessive belief in the existence of the phenomenal world (Eternalism) and excessive belief in the non-existence of the phenomenal world (Nihilism). It is intended as a golden mean – a ‘middle way’.

However, as regards this concept of ‘middle way’, it is inaccurate (quite muddle-headed, in fact) to say, as Buddhists do, that this emptiness is ‘non-dualistic’, suggesting that it literally includes all opposites, i.e. allows of effective contradiction. All that can be said is that emptiness comprises everything that is positively actual, whether in the past, present or future. Just as actuals are never contradictory, i.e. just as contradiction never occurs in reality at any time or place (not even, upon reflection, in the mind), so emptiness does not admit of contradictions. Contradiction is certainly illusory, and any claim to it is necessarily false. ‘Non-dualistic’ must be taken to mean (more accurately) unitary, undifferentiated. It refers to the actual positive, not to any imagined negative.

Often, it is implied that Emptiness corresponds to the Absolute, the Infinite, Ultimate Reality, the Original or Primordial ground of Being, or of Mind, the One, Nothingness, the Noumenon, and so forth. This concept, and some of the terminology used for it, are of course not entirely foreign to other philosophies and religions.

From its Pre-Socratic beginnings, Greek philosophy has sought for the underlying unity of the many, what lies beneath the variegated phenomenal world, the common ground of all things we commonly experience, from whence things presumably come and to which they presumably go (as it were). These ideas culminated in Neo-Platonism in late Antiquity, and returned to Western philosophy in the late Middle Ages and in the Renaissance in various contexts. Comparable notions are also found in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and of course in other Indian religions, notably Hinduism – especially in their respective more mystical undercurrents. Greek philosophy has of course influenced these various religions, and they have also demonstrably influenced each other, in this respect. There has also no doubt been influences from and to Buddhism, as the above mentioned Milinda-panha attests, being a dialogue between a Greek king and a Buddhist monk.

With regard to our bodies, or to matter in general, it is often argued that though they appear varyingly ‘substantial’ (including gases and liquids with solids), if we go deeper into their composition, as we nowadays can, we shall find mostly empty space, with only very rare particles of mass, which are just pockets of energy anyway, connected by insubstantial fields of force. But the obvious reply to that is that this would still not be total void; i.e. even if matter is not as full and substantial as it at first appears, that does not mean that there is nothing in it at all.

Nevertheless, I do not think that the Buddhist concept of emptiness applied to matter refers to this empty space with very rare substantiality. Rather, I think that it refers to the assumed universal and unitary common ground of all things, which is conceivable as pure existence, prior to any differentiation into distinct entities, characteristics or events. This root existent cannot be described or localized, because to do so would be to ascribe to it some specific character or location to the exclusion of another.

With regard to mental phenomena, by which I mean the stuff of memories and derived phantasms, which apparently occur our heads, they seem much less substantial than material ones, but nevertheless they are phenomenal insofar as we perceive them as having colors, shapes, sounds, and perhaps also (though I can’t say I am sure of it) also odors, flavors and feelings of touch. We must also in this context pay attention to concrete feelings and emotions which appear to occur in our bodies or heads, which we would collectively classify as touch-sensations.

It is worth noting the importance touch-sensations play in our view of matter: the ‘solidity’ we ascribe to matter is defined in terms of the resistance we experience when we push it, pull it or squeeze it, as well as with regard to the evident relative duration of the object at hand. No matter how much empty interspace matter may in fact contain, the experience of solidity (to various degrees) remains, and strongly determines our sense of ‘materiality’. Mental phenomena, in this context, appear far less ‘solid’ than material ones, being able to dissolve more quickly and to be relatively more malleable (and in some respects less so). The Buddhist adjective ‘empty’ should not be taken to mean ‘devoid of solidity’, for solidity (as just explained) is a phenomenological given and therefore cannot be denied.

Additionally, in my view, we must take into consideration, as mental ‘phenomena’ in an expanded sense (more precisely, ‘appearances’), objects of intuition like self, consciousness, volition and valuation, even though they are quite non-phenomenal, i.e. devoid of color, shape, sound, etc. All these existents can also, and all the more so, be regarded as empty, if we understand the concept correctly as above suggested.

According to Buddhism, this root and foundation of all existence, which is somewhat immanent as well as transcendental, can be known through meditation, or at any rate when such meditation attains its goal of enlightenment. In this, Buddhism differs from Kantian philosophy, which views the noumenal realm as in principle unattainable by the human cognitive apparatus (even though Kant[18] evidently claimed, merely by formulating his theory, quite paradoxically, to at least know of it).

Nevertheless, the two agree on many points, such as the characterization of the phenomenal realm as illusory while the noumenal is real. What is clear is that emptiness refers to a universal and unitary substratum, which is eminently calm and quiet, and yet somehow houses and even produces all the multiplicity and motion we perceive on our superficial plane. The world of phenomena rides on the noumenal like ocean waves ride on the ocean. Water and waves are essentially one and the same, yet they are distinguishable by abstraction; likewise, with regard to the noumenal and phenomenal.

Mention should be made here of the Buddhist theory of the codependence or interdependence of all dharmas. According to this theory, everything is caused by everything else; nothing is capable of standing alone. That precisely is why everything (i.e. all things in the world of phenomena) may be said to be empty – because it has no ‘own being’ (svabhaha). This means that not only we humans, and all sentient beings, are empty of self, but even plants and inanimate entities are empty. This may sound conceivable at first blush, but the notion of interdependence does not stand serious logical scrutiny. The claim that everything is a cause of everything is a claim that there is at least a partial, contingent causative relation between literally any two things. But such causative relation must needs be somewhat exclusive to exist at all[19]. So, the idea put forward by Buddhist philosophers is in fact fallacious, a ‘stolen concept’.

It should also be said that the term ‘emptiness’, insofar as it is intended negatively, i.e. as indicative of privation of existence, is necessarily conceptual. We can say that being comes from and returns to non-being, but it must be acknowledged that this is something that cannot be known by direct experience, whether ordinary or meditative, but only by conceptual insight. The simple reason for this is that negation cannot be an object of perception or intuition, but can only be known by inductive inference from an unsuccessful search for something positive[20]. Only positives can be experienced. All negative terms are, logically, necessarily conceptual; indeed, negation is one of the foundations of conceptual thought. Thus, any claim that one has purely experienced, in the most profound levels of contemplation, the Nothingness at the root of Existence, is not credible: reasoning (even if wordless) was surely involved.

For Buddhism, the original ground is something impersonal, though some might view it as a sort of pantheism. For the above mentioned major religions, the original ground is identified with God. In my opinion, such identification is more credible, because I do not see how the conscious, willful, and valuing individual soul could emerge from something greater that is not itself essentially conscious, willful, and valuing. These faculties being higher than impersonal nature, their ultimate source must potentially have them too. In Jewish kabbalah, for instance, the human soul is viewed as a spark of the Divine Soul (a chip off the old block as it were). We are in God’s image and likeness in that, like Him, we have soul, cognition, volition and valuation, although to an infinitesimal degree in comparison to His omniscience, omnipotence and all-goodness. But in any case, it is clear that there is some considerable agreement between the various philosophies and religions.

(c) Let us now consider soul in the context of emptiness. Is the concept of self or soul logically compatible, or (as the Buddhists claim) incompatible, with that of emptiness? Can a soul find liberation from its limitations and suffering, or is it necessarily stuck in eternal bondage to birth and death, deluded by endless grasping and clinging to things of naught? Is liberation only possible by giving up our belief the soul? If the answer to these questions is in accord with Buddhism, the five skandhas doctrine would seem to be useful; but if a soul can (through whatever heroic efforts of spiritual practice) extricate itself from the phenomenal and reach the noumenal, then that doctrine would seem to be, at best, redundant, if not ridiculous.

Consider, first, a temporary soul (whether its existence is limited to one lifetime or it spans several lifetimes, either in a body or disembodied). Such a soul, necessarily, like all other impermanent existents that have a beginning and an end, has come from emptiness and will return to emptiness; it is created and conditioned, by the uncreated and unconditioned One. Moreover, a temporary soul might even be regarded as eternal in the sense that it has a share in eternity, not only when it temporarily exists manifestly as a distinct entity, but even before its creation and after its apparent destruction, when it is still or again an undifferentiated part of the original ground. So, no problem there, other than finding out precisely how to indeed liberate it (no mean feat, of course).

A problem might rather be found with regard to an eternal soul, and this is no doubt what caused Buddhists to be leery of the very idea of self (which they regarded as necessarily eternal, remember). The problem is: if the individual soul (or anything else, for that matter) stands side by side with the ultimate reality throughout eternity, then how can it ever merge with it? No way to liberation would seem conceivable for a soul by definition eternally separate from emptiness. But even here, we could argue that the separation of the distinct soul from the universal unitary matrix is only illusory; i.e. that all through eternity this indestructible soul is in fact a constant emanation from the abyss and really always imbedded in it. What makes an illusion (e.g. a mirage or a reflection) illusory is not how long it lasts (a split second or a billion years), but its relativity (a mirage is due to refraction of light from an oasis, a mirror image of the moon is due to reflection of light from the moon). So, in truth, even an eternal soul can conceivably be reconciled with emptiness. I am not affirming the soul is necessarily eternal in that sense, but only pointing out that it conceivably could be so.

In conclusion, the skandhas idea serves no purpose with regard to the requirement of emptiness. Indeed, it is highly misleading, since it is based on false assumptions concerning other doctrinal possibilities. Buddhists cling to this idea for dear life, but without true justification. Clearly, the position taken here by me is that logically we can well claim that people have a soul, and reject the orthodox Buddhist belief that what we call our self is nothing but a cluster of passing impersonal events, without giving up on the more metaphysical doctrine that at the root of spiritual (i.e. every soul’s) existence there is ‘emptiness’ as here understood.

Just as we can say that apparently substantial material, or concrete mental, phenomena are ultimately empty, so we can say that the soul each of us consists of is ‘substantial’ in its own rarified, spiritual way and at the same time ultimately empty, i.e. at root just part of the universal and unitary ground of all being. In other words, contrary to what Buddhist philosophers imagined, it is not necessary to deny the existence of the soul in order to affirm its ‘emptiness’, any more than it is necessary to deny the existence of the body or mind in order to affirm their ‘emptiness’. That is to say, there is no logical necessity to adopt the five skandhas idea, if the purpose of such position is simply to affirm ‘emptiness’.

4. In Conclusion

The fact of the matter is that the no-soul thesis is riddled with contradictions. We are told by Buddhists that we can find liberation, but at the same time that we don’t even exist. We are told to be conscious, but at the same time we are denied the power of cognition – i.e. that the soul is the subject of cognitive events. We are told to make the effort to find liberation, but at the same time we are denied possession of volition – i.e. that the soul is the free agent of acts of will. We are told to make the wise choices in life, but at the same time we are denied the privilege of value-judgment – i.e. that the soul is capable of independent and objective valuation.

The no-soul thesis is upheld in spite of these paradoxes, which were well-known to Buddhist philosophers from the start. What is the meaning of spirituality without a spirit (soul, self)? Who can be liberated if there is no one to liberate? Why and how engage in spiritual practice if we not only do not exist, but also have no power of consciousness, volition or valuation? Why bother to find release from suffering if we do not really suffer? Who is writing all this and who is reading it? The no-soul thesis simply cannot be upheld. The soul can well be claimed to be ultimately ‘empty’ in the aforesaid sense, but the thesis of five skandhas instead of a soul is logically untenable.

We have seen that the five skandhas doctrine cannot be regarded as an accurate description of the human psyche in its entirety. It is not a thorough phenomenological account, since it ignores mankind’s major higher faculties – intelligence, rationality and freewill. It focuses exclusively on some petty aspects of human psychology, the five skandhas, without openly acknowledging the more noble side of humanity, which makes liberation from such pettiness possible. It has metaphysical pretensions, with ontological and epistemological implications – notably, the idea that we are empty of soul, devoid of personality – but it turns out that this idea does not stand up to logical scrutiny, being based on circular arguments and foregone conclusions.

Thus, whereas the five skandhas thesis may have at first seemed like an important observation and idea, which applied and buttressed the more general Buddhist thesis of emptiness, and at the same time provided a spiritually useful description of human psychology, it turns out to be a rather limited and not very well thought-out creed. This does not mean that it has no worth at all, but it does mean that it is far less important than it is made out to be.

This being said, I hasten to add that the present criticism of this one doctrine within Buddhist psychology and philosophy is not intended as a blanket belittling or rejection of Buddhist psychology and philosophy. Certainly, Buddhist psychology and philosophy have a great deal more to offer the seeker after wisdom than this one doctrine. It is rich in profound insights into the human psyche and condition, which every human being can benefit from. This is evident already in the opening salvo of Buddhist thought, the Four Noble Truths, which acknowledge the human condition of suffering and identify the psychological source of such suffering in clinging to all sorts of vain things, and which declare the possibility of relief from suffering through a set program of spiritual practices.

In the Buddhist conception of human life, our minds are poisoned by numerous cognitive and volitional and emotional problems. At the root of human suffering lies a mass of ignorance and delusion about oneself and the world one suddenly and inexplicably finds oneself in. These give rise to all sorts of unwise desires, including greed (for food, for material possessions) and lust (for sexual gratification, for power), and aversions (fears, hatreds). The latter impel people to act with selfishness (in the more pathological sense of the term), and in some cases with dishonesty or even violence (coldness and cruelty), and generally with stupidity. But Buddhism proposes ways to cure these diseases, so its outlook is essentially positive.

Clearly, Buddhism has a particularly ‘psychological’ approach to life. It is also distinguished by its businesslike, ‘no blame’ approach to spirituality, which is no doubt why many people in the West nowadays are attracted to it. Unlike most of the other major religions, notably Judaism and its Christian and Islamic offshoots, it does not try to make people feel guilty for their sins, but rather encourages them to deal with their problems out of rational self-interest. It is thus less emotional and more rational in many ways.

Judaism too, for instance, includes psychological teachings, although perhaps to a lesser extent. One of the main features of Judaic psychology is the idea that humans have two innate tendencies – a good inclination (yetzer tov) and a bad inclination (yetzer ra’)[21]. These two inclinations influence a person for good or for bad in the course of life (physical life and spiritual life), but they never control one, for human beings are graced with freewill. This means that come what may, a man or woman is always (at least, once adult) responsible for his or her choices. This ethical belief in freedom of choice and personal responsibility is present in Judaism since its inception, as the following Biblical verse makes clear: “Sin coucheth at the door; and unto thee is its desire, but thou mayest rule over it” (Gen. 4:7)[22]. Knowing this, that one indeed has freedom of will, one can overcome all bad influences and forge ahead towards the eternal life.

In Buddhism, we may discern a similar possibility of taking full responsibility for one’s life in the very first chapter of the Dhammapada (1:1-2). “If a man speaks or acts with an impure mind, suffering follows… If a man acts with a pure mind, joy follows.” Although the five skandhas doctrine gives people the impression (as shown above) that they are not responsible for their deeds, we see here that this is not really the message of Buddhism, which generally enjoins strong spiritual effort in the direction of self-liberation and thence of liberation for all sentient beings.

Drawn from a yet to be published work, this essay was first posted in 2016 as a preview on the author’s blog.

[1] According to the Wikipedia article on this topic, the American Buddhist monk Thanissaro, in Handful of Leaves, Vol. 2, 2nd ed. 2006, p. 309, alleges that the Buddha “never defined a ‘person’ in terms of the aggregates” and that this doctrine is not pan-Buddhist. To my mind, if he said that (I have not seen it with my own eyes), he may well be right.

[2] I have often in my past writings pointed out the vagueness of the terms mind and consciousness in the discourse of Buddhist philosophers, and explained there how it allows them to get away with much fallacious reasoning.

[3] Note that in my listing, samjna is placed after samskara, which is not the usual order of listing. I could also have placed samjna after vijnana, since the latter category adds objects of cognition to be considered by the former. However, vijnana also has samjna as one of its objects, since the latter involves consciousness and a conscious subject; so the chosen order of presentation seems most logical.

[4] One that could be, and no doubt is, used in meditation.

[5] It is interesting to note in passing how modern physicists, biologist, psychologists and philosophers tend to similarly studiously ignore the human soul and its functions of cognition, volition and valuation, in their respective accounts of the world, life and humanity. But whereas Buddhism’s motive is to protect its dogma of no-self, the motive of modern ‘scientists’ is to protect their dogma of universal materialism and determinism. The intellectual sin involved in both cases is to deliberately make things look simpler than they are so as to make them fit more easily into one’s pet theory.

[6] Quoted or paraphrased (not clear which) in Buddhist Scriptures, edited by Edward Conze. Vasubandhu was a Buddhist monk and major philosopher, fl. 4th to 5th cent. CE in Ghandara (a kingdom located astride modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan). His philosophical posture is today normative, at least among the Mahayana, but it was opposed by a Hinayana school called the Personalists, which lasted for many centuries as of 300 BCE and involved a good many monks (e.g. an estimated 30% of India’s 200,000 monks in the 7th cent.). See pp. 190-197.

[7] Modern ‘scientists’ (I put the word in inverted commas deliberately, to signify criticism) would say much the same, but would place the electrical disturbances on the more physical plane of the brain and nervous system. The idea that the mind is a sort of very sophisticated computer is untenable, for exactly the same reasons that the idea of skandhas is untenable.

[8] One Victoria Lavorerio, in a paper called “The self in Buddhism,” has written: “If following Descartes we say that where there is a thought there is a thinker, the Buddhist would respond ‘where there is a thought, there is a thought’.” While rather witty, this statement is of course inane, since its author does not grasp the logical absurdities of the Buddhist no-soul thesis (and that, even though she quotes a couple of arguments of mine regarding them), but merely seeks to position herself fashionably. See her essay here: http://www.academia.edu/1489808/The_self_in_Buddhism.

[9] I assume that the Yogacara, Mind-Only, school would advocate that matter is a sort of mental phenomenon. In that case, they would presumably advocate that the skandhas theory concerns not only personality but the whole phenomenal world.

[10] It is worth noting, of course, that the fact that this simplistic, though ancient and widespread, theory of physics (with reference to the ‘elements’ of earth, air, fire and water, or similar concepts) is advocated by Buddhism is proof that this doctrine is not the product of any ‘omniscience’. If the Buddha indeed formulated it or accepted it, he cannot be said to have been ‘omniscient’ since this is not an accurate account of the physical world. This being the case, it is permitted to also doubt he was ‘omniscient’ in his understanding of the mental or spiritual world. Of course, it could be argued that he appealed to the four elements theory only because it was commonly accepted in his day, in the way of a ‘skillful means’, without intending to endorse it.

[11] Given in full in Thich Nhat Hanh’s The Heart of Understanding (Berkeley, Ca.: Parallax Press, 1988).

[12] See Conze, pp. 147-151. The dialogue is given in full here. Milinda (Gk. Menander) was the “Greek ruler of a large Indo-Greek empire [namely Bactria] in the late 2nd century BC.” Nagasena was a senior Buddhist monk. The text was, according to EB, “composed in northern India in perhaps the 1st or 2nd century AD (and possibly originally in Sanskrit) by an unknown author.”

[13] Similarly, a river, though not man-made, can be defined by means of abstractions. This is said with reference to the analogy proposed by EB earlier on.

[14] For instance, in the Hindu Bhagavad-Gita, the atman (individual soul) is said by Krishna to be: “unborn, undying; never ceasing, never beginning; deathless, birthless; unchanging for ever.” (The Song of God: Bhagavad-Gita. Markham, Ont., Canada: Mentor, 1972.)

[15] In Conze, again (p. 195).

[16] Korea, 1158-1210.

[17] Classics of Buddhism and Zen, vol. 1. Tr. Thomas Cleary. Boston: Shambhala, 2005. Pp. 417-419, 424.

[18] Immanuel Kant (Germany, 1724-1804).

[19] See my The Logic of Causation, chapter 16.3, for a full refutation.

[20] See my Ruminations, chapter 9.

[21] This two-inclinations psychological thesis of course stands in contrast to three other theses: that humans have only a good inclination (optimism), or only a bad inclination (pessimism), or no natural inclination at all (neutrality). This is an interesting issue that deserves a longer discussion. The difference between these four theses is moot, if we consider that all this is about influences on the soul, and not about determinism or fatalism; the soul remains free to choose whether influenced one way or the other to greater or lesser degree. I think the point of the Jewish doctrine is simply this: to make the individual aware that he is constantly under pressure from influences of various sorts, some good and some bad, and that he is wise to at all times identify with the positive ones and avoid identifying with the negative ones; i.e. to regard the true ultimate desire of his soul as the good and to regard the bad as delusive nonsense.

[22] The idea of ‘inclination to evil’ may also be traced to the Bible, namely to Gen. 8:21, which quotes God as stating that “the inclination of man’s heart is evil from his youth.” (That is said after the Deluge; earlier, in Gen. 6:5, it is said more pessimistically that “every inclination of the thoughts of his [man’s] heart is only evil all through the day.” Commentators explain the difference by suggesting that the Deluge made man wiser. Maybe the difference between the terms “the inclination of man’s heart” and the “inclination of the thoughts of man’s heart” has some significance.)